Air-Hardening Cold-Work Tool Steels

The air-hardening cold-work tool steels, designated as group A steels in the AISI classification system, achieve their processing and performance characteristics with combinations of high carbon and moderately high alloy content. The high alloy content is sufficient to provide not only air-hardening capability, but also a distribution of large alloy carbide particles superimposed on the microstructures developed by heat treatment processing. The alloy carbides have very high hardness relative to martensite and cementite, thus con- tribute to enhanced wear resistance of A-type steels compared to tool steels of lower alloy content Although the alloy content is high and the A-type steels have good temper resistance with demonstrated secondary hardening, their hot hardness relative to other even more highly alloyed tool steels is not sufficient for high-speed machining or hot-work applications; as a result, the A-type tool steels are still largely used for cold-work applications.

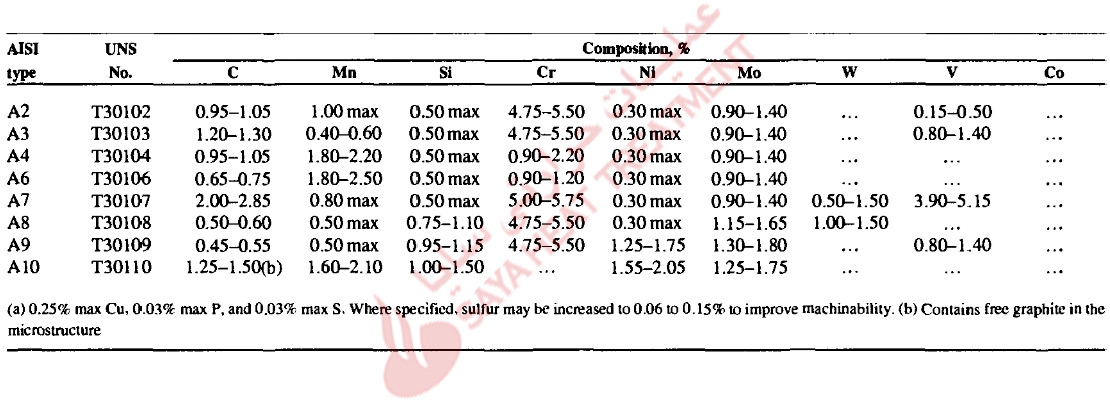

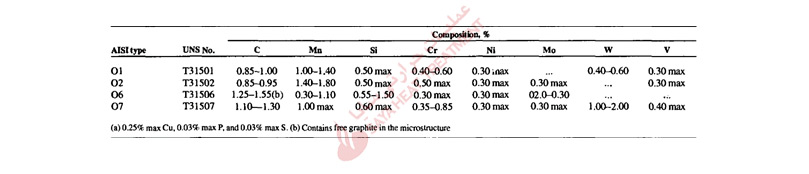

Table 11-1 presents the nominal chemical compositions of the A-type tool steels. A major processing advantage of these steels, compared to tool steels that must be water or oil quenched, is that air hardening produces minimum distortion and very high safety and resistance to cracking during hardening. Various combinations of manganese, chromium, and molybdenum contents make possible the air-hardening capability of the A-type steels. Table 11-1 shows that many of these steels are alloyed with about 5% Cr, but others, such A4, A6, and A10, have high manganese contents and lower chromium contents. The latter adjustment in composition permits the use of lower austenitizing temperatures for hardening, which in turn further reduces dimensional changes and minimizes undesirable surface reactions such as decarburization during hardening.

Silicon is a major alloying element in the A8, A9, and A10 steels and helps to promote toughness, in combination with the high carbon contents of A10 steel, silicon promotes graphite formation. The graphite content of A10 steel makes it highly machinable in the annealed condition, and in the hardened condition, the graphite contributes to galling and seizing resistance at tool steel die/workpiece interfaces. Type A7 is the most highly alloyed of the A-type tool steels, and earlier merited a classification of its own as a special wear-resistant cold work die steel. The tungsten and high vanadium contents of A7 steels, combined with high carbon content, produce high volume fractions of alloy carbides; these promote very high wear resistance and good hot hardness, but low toughness.

Hardenability and hardening

Preheating at temperatures about 650 to 675 °C (1200 to 1250 °F) reduces soaking time and the time for decarburization, to which the A-type steels are highly susceptible because of their high carbon content.

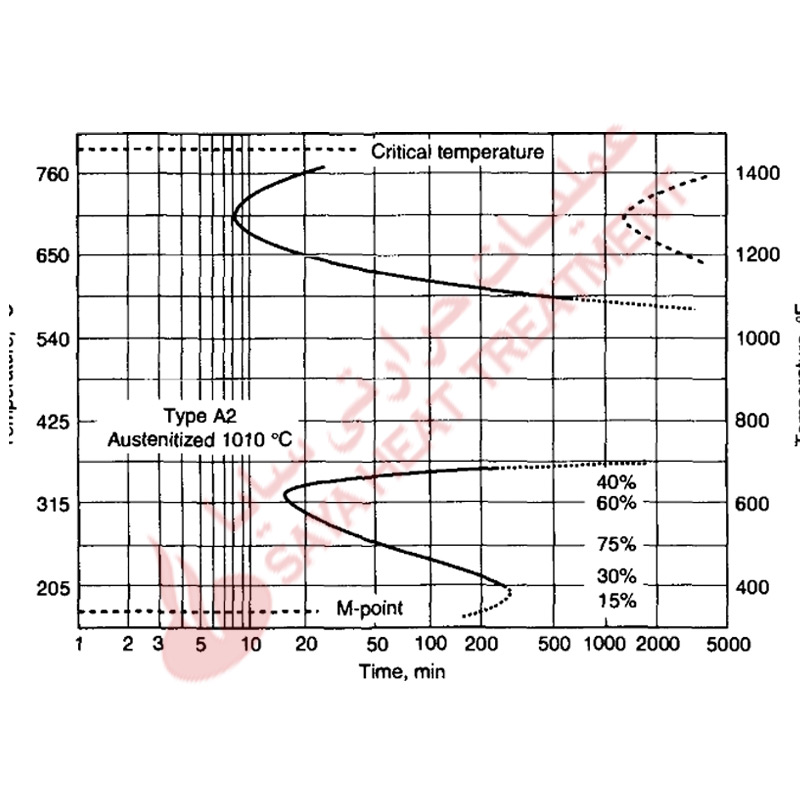

The alloy content of the A-type tool steels severely retards the transformation of austenite to ferrite-carbide microstructures. Figure 11-1 shows an IT diagram for an A2 steel austenitized at 1010 °C (1850 °F). Two well-defined C-curves, one for pearlite and the other for bainite, characterize the austenite decomposition. The A-type tool steels are susceptible to decarburization during austenitizing for hardening, and significant decarburization will lower the surface hardness of hardened parts. Tools should be heated in vacuum, or in salt baths, fluidized beds, or furnaces with neutral or slightly carburizing atmospheres. The rate of decarburization increases with both time and temperature; and decarburization can also be minimized by preheating, which will minimize soaking time at high austenitizing temperatures where decarburization most rapidly develops.

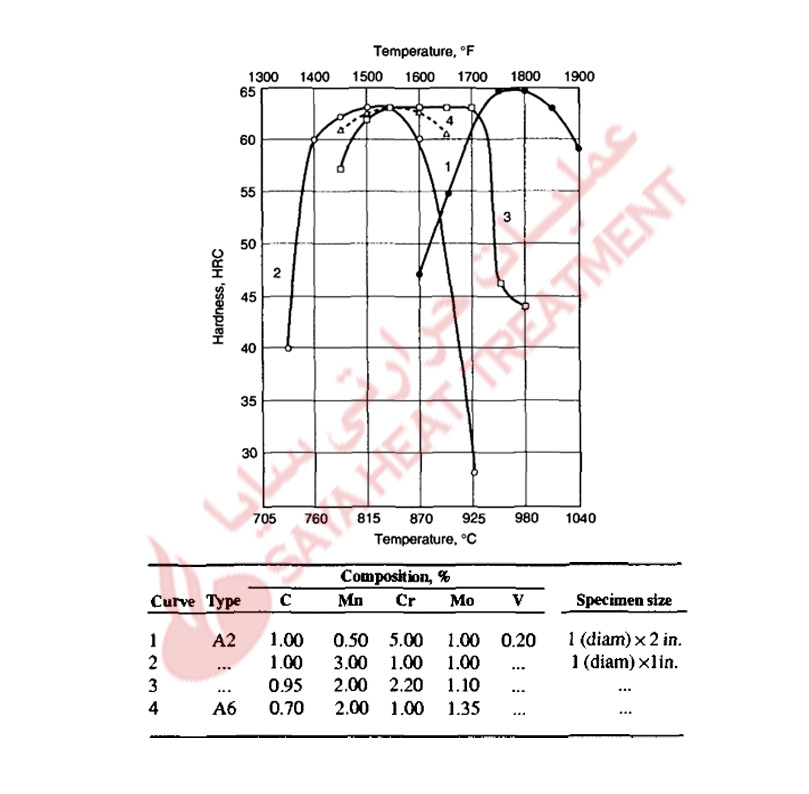

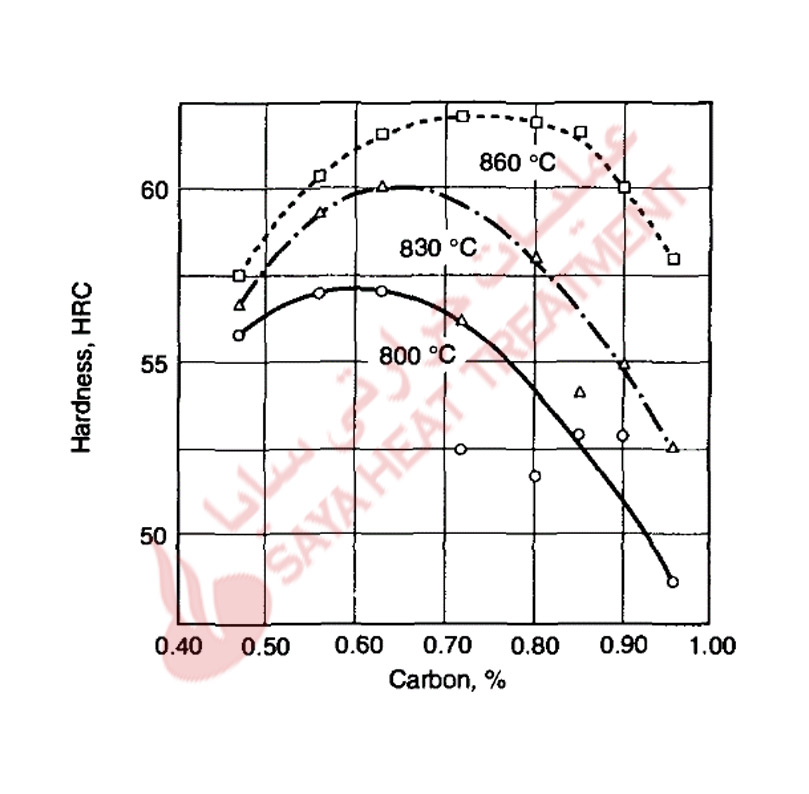

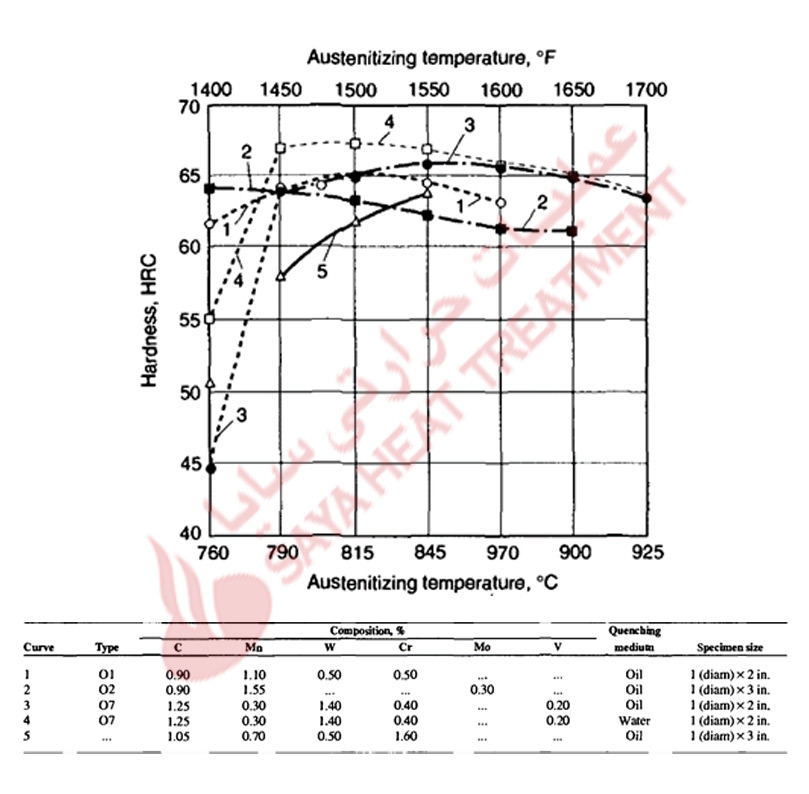

Proper control of austenitizing is critical for the achievement of optimum hardened microstructures and properties in the air-hardened cold-work tool steels. Too low an austenitizing temperature will reduce hardness because of the formation of nonmartensitic microstructures during air cooling. too high an austenitizing temperature will cause too high a content of carbon and alloying elements to dissolve in austenite, lowering M s temperatures and reducing hardness because of excessive retained austenite in the hardened microstructures. These effects of austenitizing produce parabolic curves of as-quenched hardness versus austenitizing temperature, as shown in Fig 11-2 for several A-type steels. The A2 steel with 5% Cr addition requires a higher austenitizing temperature to produce peak as-cooled hardness, whereas the steels with major additions of manganese develop peak hardness after austenitizing at lower temperatures. Figure 11 -3 shows hardness as a function of carbon content for air-cooled A4 steels austenitized at various temperatures. For medium carbon contents, the effect of austenitizing on hardness and hardenability is relatively low because all the carbon and alloying elements are put into solution at low austenitizing temperatures. In the high-carbon steels, the effect of austenitizing temperature is much greater; higher temperatures are required to dissolve the higher quantities of carbides present in these steels after annealing. The results shown in Fig. 11-3 led to the development of A6 steel, which has just sufficient carbon to attain 62 HRC after hardening at the relatively low austenitizing temperature of 875 °C (1575 °F).

Tempering

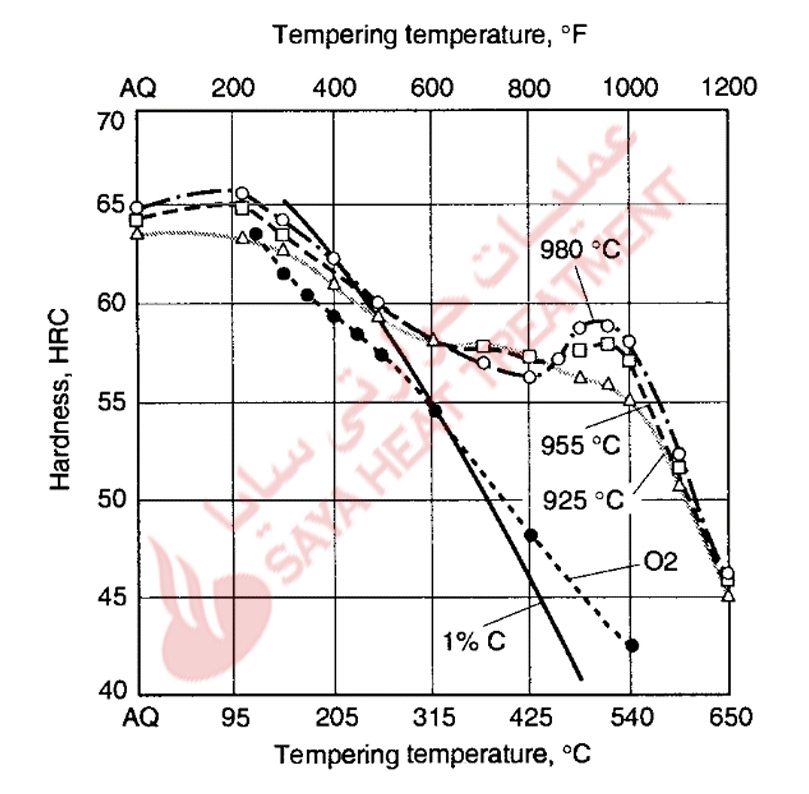

Figure 11-4 shows hardness as a function of tempering temperature for an A2 steel austenitized for hardening at three temperatures, an 02 steel, and a plain carbon steel containing 1 % C. The tempering resistance of the A2 steel is much higher than that of the plain carbon and 02 steel, and a definite but small secondary hardening peak develops in the A2 steel after tempering at about 510 °C (950 °F). The hardness increase due to secondary hardening is highest in specimens hardened at the highest austenitizing temperature. In those specimens, the super saturation of the martensite with carbon and alloying elements is higher than in specimens austenitized at lower temperatures; consequently, the precipitation of alloy carbides at the higher tempering temperatures is most intense.

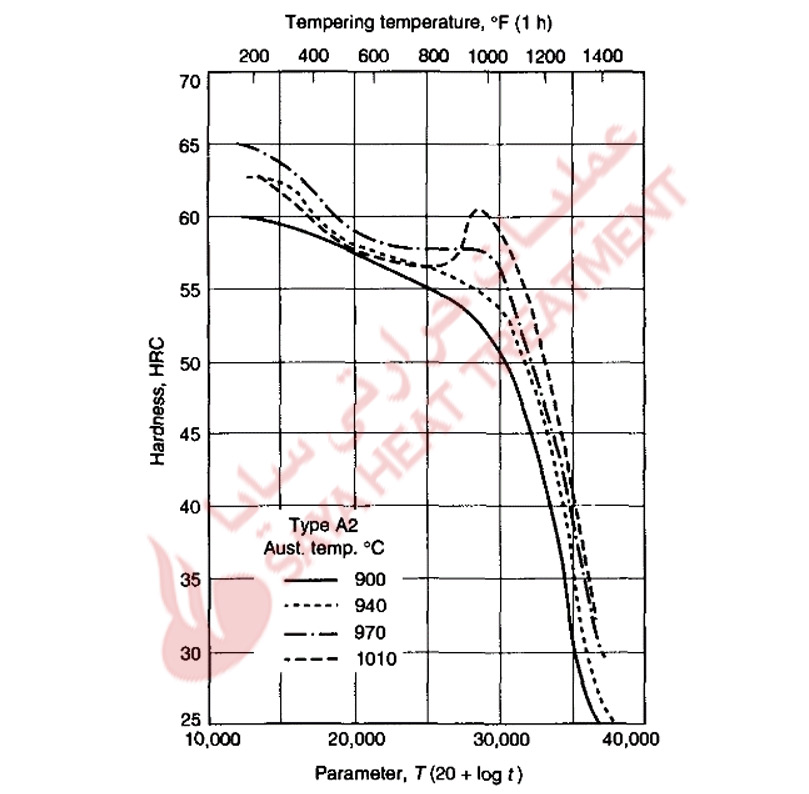

Figure 11-5 plots hardness of an A2 steel austenitized at several temperatures as a function of a time-temperature parameter developed by Hollomon and Jaffe and extended to tool steels by Roberts et al. The fact that logarithm of time is used in the parameter reflects the fact that time has a smaller effect on tempering changes than does temperature.

The retained austenite content of hardened air-hardening steels may be quite high. The retained austenite is thermodynamically unstable at temperatures below the Ai and, must transform to more stable combinations of phases during what is known as the second stage of tempering. In highly alloyed tool steels, austenite transformation may take place in two stages, each with its own set of kinetics.

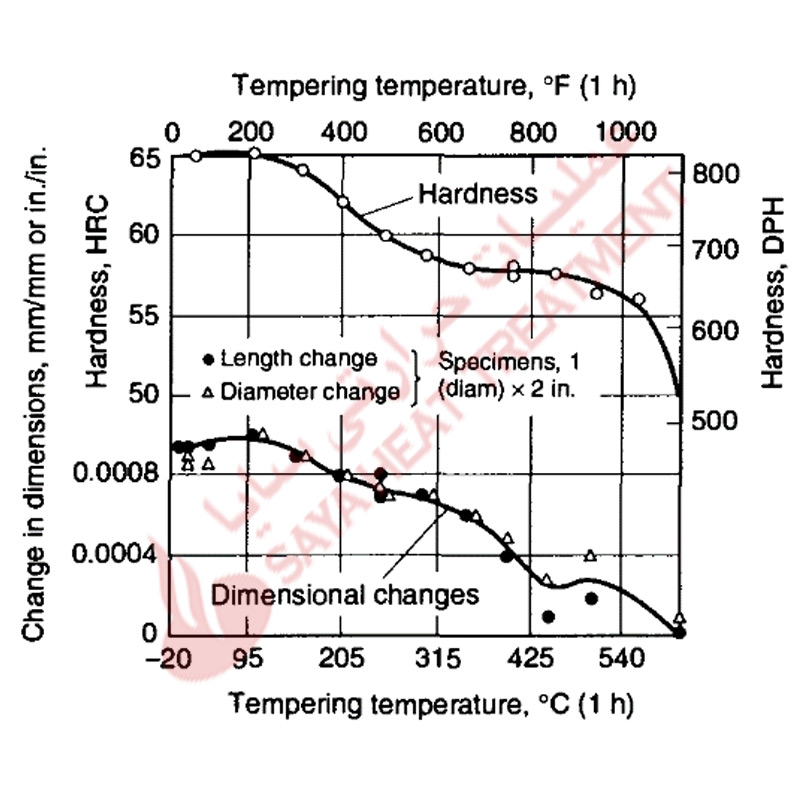

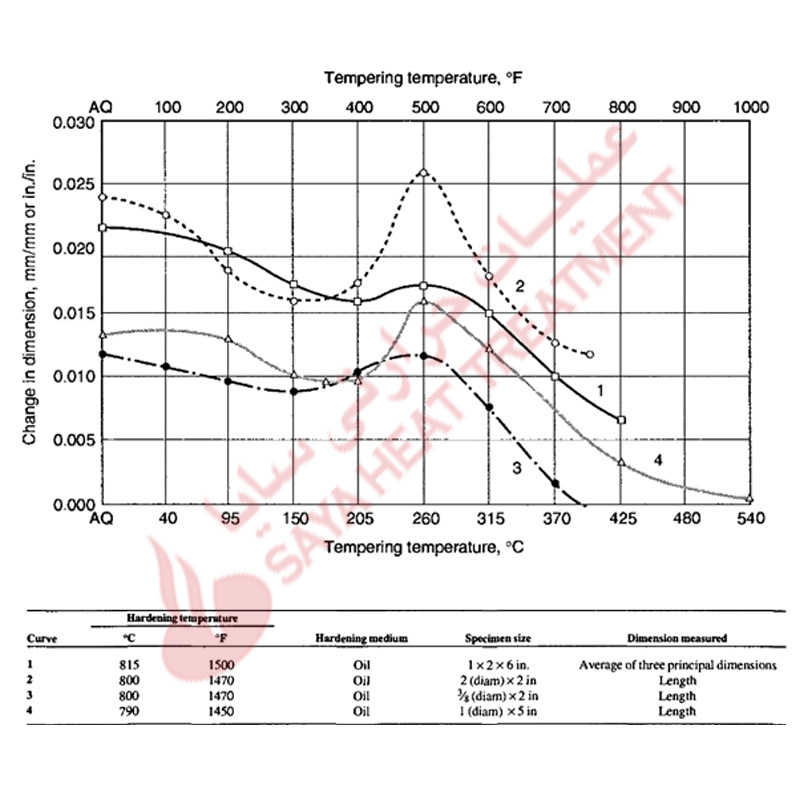

The dimensional changes caused by hardening and tempering A-type tool steels are shown in Fig 11-6 and 11-7. In carbon tool steels the increase in volume due to hardening may be 0.7% of the as-annealed volume, but the volume changes are reduced in tool steels alloyed with chromium. Scott and Gray measured an expansion of 0.001 in all directions of a fully hardened steel containing 1% C and 5% Cr, and showed (Fig 11-6) essentially continuous contraction of the dimensions in a hardened A2 steel with increasing tempering temperature.

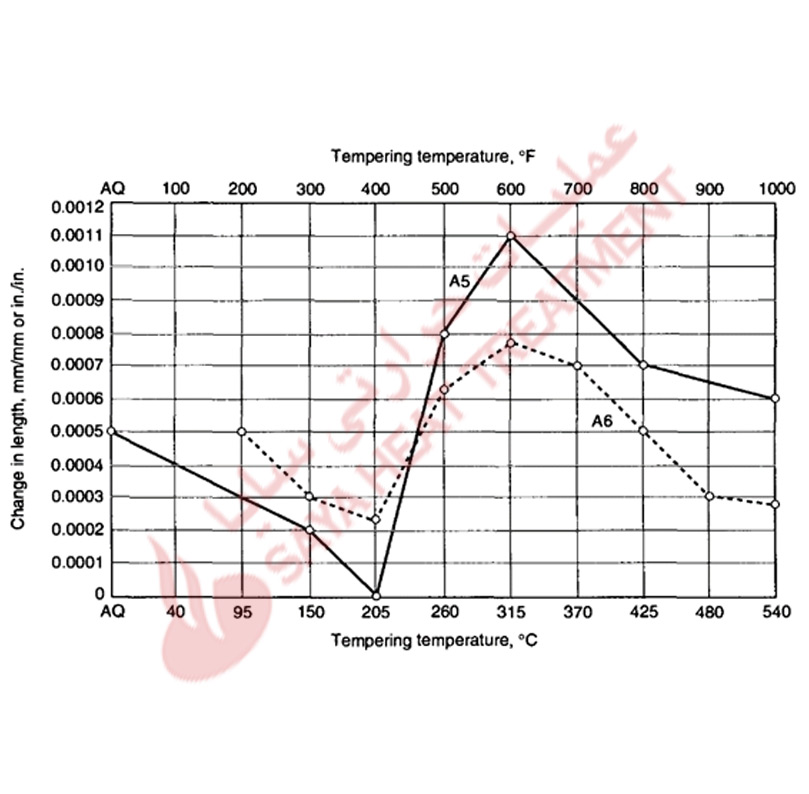

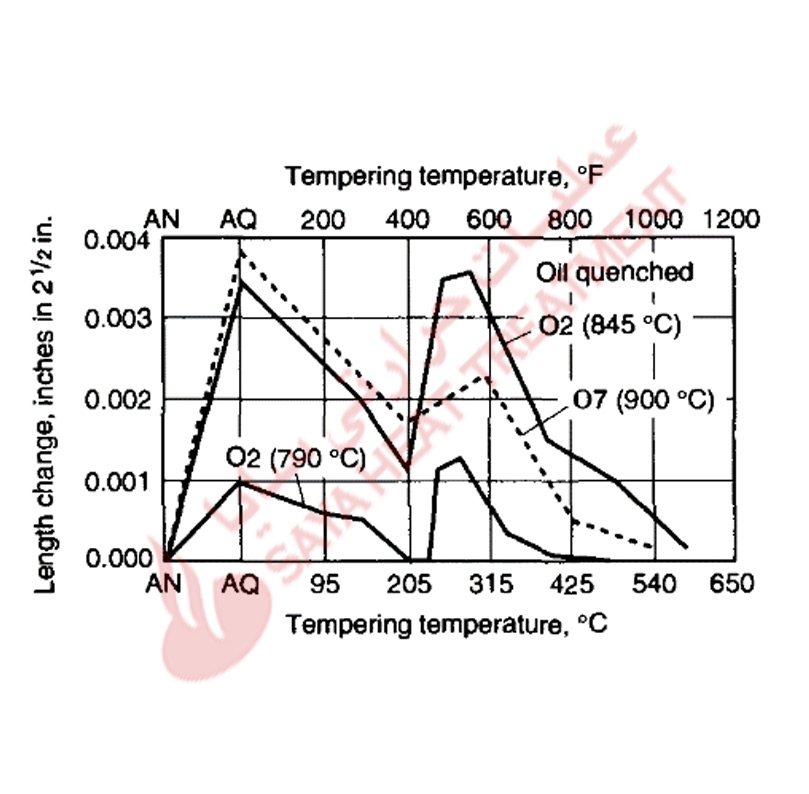

As discussed, retained austenite may be a significant component of the hardened microstructures of A-type steel, and can be controlled by austenitizing, refrigeration, and tempering. For a given hardened structure, transformation of retained austenite during tempering is accomplished at temperatures where hardness may be significantly reduced and where the transformation of the austenite may cause significant dimensional changes (Fig 11-7).